President Trump signed the federal reconciliation bill, or H.R. 1, into law on July 4, 2025. The bill has numerous provisions that will be harmful to the health and human services and will negatively affect communities across the country. While there are many programs that will be impacted by the harmful changes included in the legislation, with the key provisions affecting the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Medicaid, and Medicare.

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

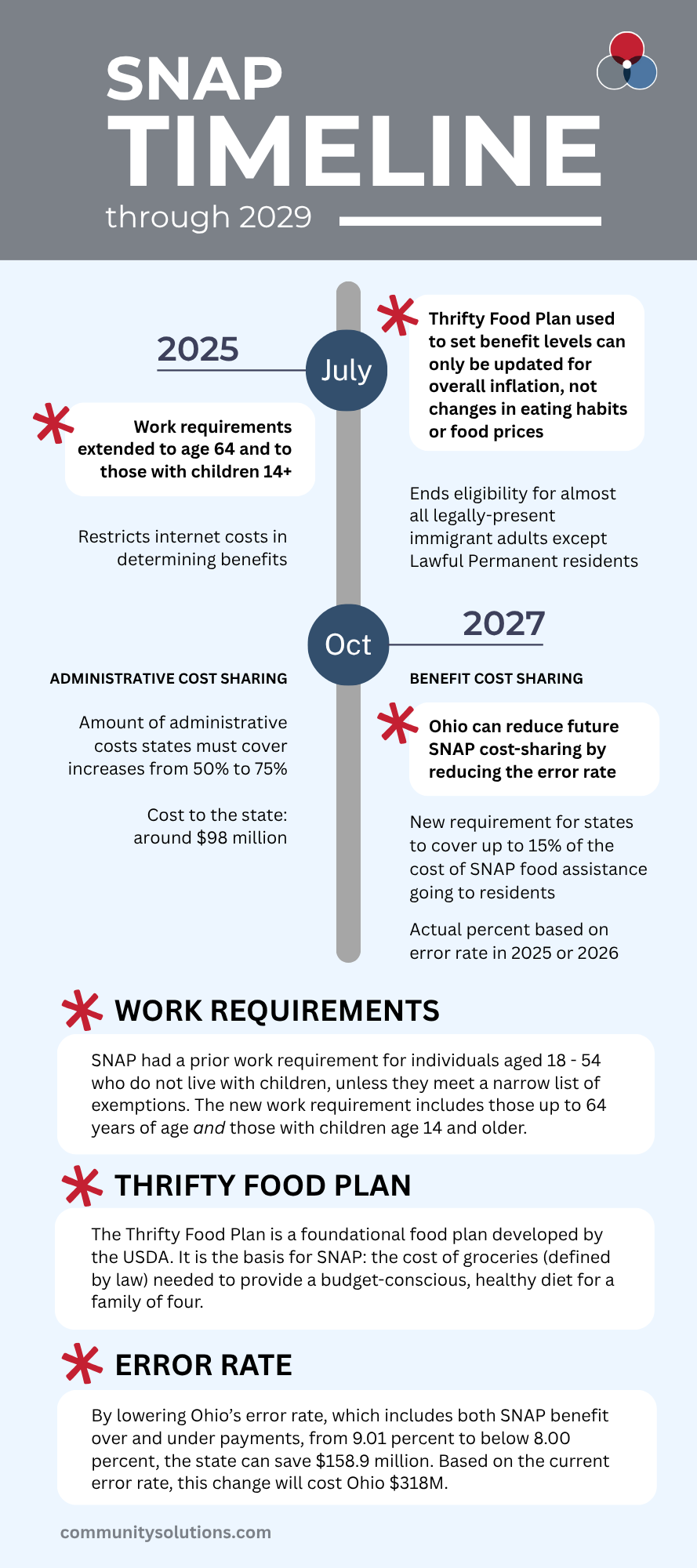

The changes to SNAP included in the bill will undermine the effectiveness of our nation’s most effective anti-hunger program. The first change is operating the SNAP program will become much more expensive for states. Previously, the federal government covered 100% of the cost of SNAP benefit payments, which go directly to eligible families to help cover the cost of groceries, and 50% of administrative costs. Now, states will pay between 5% and 15% of the SNAP benefit costs, unless they can achieve a payment error rate below 6%, and 75% of the administrative costs. According to Federal Funds Information for States (FFIS), these two changes will cost Ohio an additional $416 million a year, $318 million of which will be from the new SNAP benefit payment cost sharing provision and $98 million from the new administrative cost sharing provision.

In addition, the bill imposes harsh new work requirements on older adults and parents.

SNAP already has a strict work requirement for individuals between the ages of 18 and 54 who do not live with children unless they meet a narrow list of exemptions.

The legislation extends this requirement to older adults up to age 64, to parents with children aged 14 and older, and eliminates exemptions from the three-month time-limit for veterans, individuals experiencing homelessness, and former foster youth.

These SNAP changes will cause approximately 717,000 families in Ohio lose some or all their SNAP benefits.

Medicare eligibility restrictions

The federal reconciliation bill also includes provisions that will affect those on Medicare. One key Medicare provision is the restriction of who is eligible for Medicare.

The bill restricts Medicare eligibility to citizens, green card holders, certain immigrants.

It ends eligibility for people not included in the above groups, such as those with temporary protected status and refugees and asylees. Anyone who no longer qualifies for Medicare benefits but is currently receiving benefits will have their benefits terminated no later than January 2027.

The bill also makes changes to a 2023 rule that works to reduce barriers to enrollment for Medicare beneficiaries in Medicare Savings Programs, which provides Medicaid coverage of Medicare premiums and cost sharing for low-income Medicare beneficiaries. The bill will delay implementation of the rule until October 2034, except for provisions that have already taken effect, including auto-enrollment of certain Supplemental Security Income recipients.

Enrollment barriers could cause at least 178,000 Ohioans with Medicare to lose cost-sharing help.

The final provision in the bill related to Medicare that will be covered is related to nursing homes. In April 2024, a final rule was adopted that requires long-term care facilities to meet minimum staffing levels for registered nurses and nursing aides. While the minimum staffing requirements were overturned by the US District Court for Northern Texas, the bill prohibits the Secretary of Health and Human Services from implementing, administering, or enforcing the minimum staffing levels required by the final rule until October 1, 2034. Only 10% of facilities in Ohio met all aspects of the minimum staffing requirements.

Medicaid Expansion, work requirements, and financing

The bill includes many provisions related to Medicaid, but the focus will be on those which broadly fall under three different topics. They are Medicaid Expansion, work requirements, and financing.

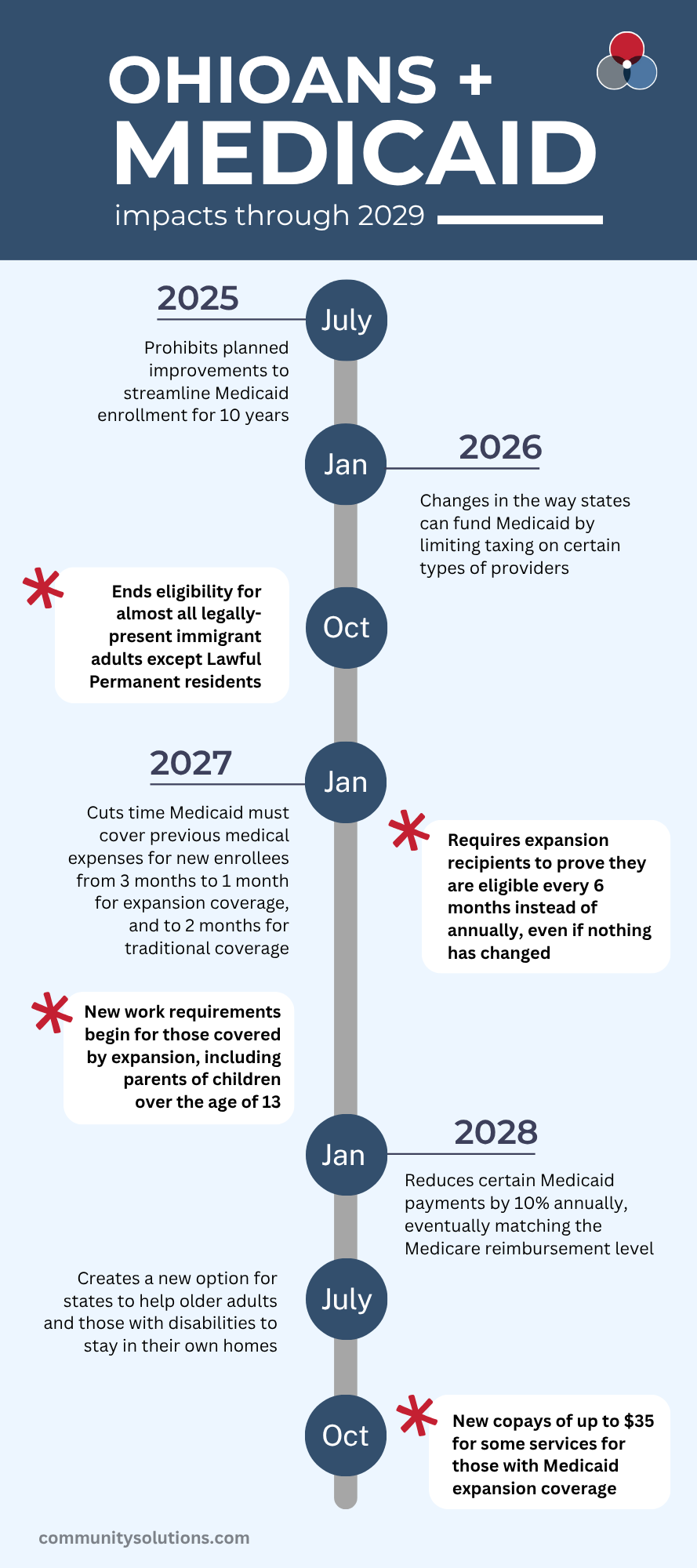

Medicaid Expansion

The Affordable Care Act expanded Medicaid eligibility to non-elderly adults with incomes up to 138% Federal Poverty Level (FPL) based on modified adjusted gross income and provided 90% federal financing for the expansion population. The bill requires that, starting in Federal Fiscal Year (FFY) 2029, states impose cost sharing of up to $35 per service on expansion adults with incomes 100-138% FPL, with a handful of exempted services.

States will have to conduct eligibility redeterminations at least every 6 months for Medicaid expansion adults instead of once every 12 months.

Work requirements

The bill requires states, no later than December 31, 2026, to make 80 hours per month of work or qualifying activities a requirement for individuals between the ages of 19 and 64 to qualify for Medicaid under the expansion population. It exempts those from the work requirement who are medically frail or parents with children aged 13 and under. These work requirements cannot be waived by Section 1115 waivers.

If a person is denied or disenrolled due to work requirements, they are also ineligible for subsidized Marketplace coverage.

Financing

One of the biggest changes to Medicaid financing in the bill is the changes to provider taxes. Provider taxes, which are taxes on hospitals, nursing facilities, managed-care organizations, and other entities, are commonly used to fund a state’s share of Medicaid. Under current law, provider taxes are capped at 6 percent of net patient revenues. The bill prohibits states from establishing any new provider taxes or from increasing the rates of existing taxes and reduces the allowable limit of provider taxes by 0.5% annually starting in FFY 2028 until it reaches 3.5% in FFY 2032.

The bill also directs the Department of Health and Human Services to revise state directed payment regulations. State-directed payments (SDPs) allow managed-care plans to channel added funding to hospitals for improved quality of care, behavioral health, obstetrical care, and other community priorities. Currently, the upper limit for SDPs is set at the average commercial insurance rate, which are typically the highest reimbursement rates; the new proposal would cap these payments at published Medicare rates, which typically fall between commercial and Medicaid rates, for any SDP adopted after enactment.

Although existing SDP agreements remain grandfathered, states could neither increase them nor expand into new programs without strict preapproval.

Over time, this freeze would fail to keep pace with rising health-care costs, further widening the gap between Medicaid reimbursements and actual hospital expenses.

The Center for Community Solutions will continue to report on changes in federal legislation that affects health and human services provided to Ohioans.