The Rural Health Transformation (RHT) Program aims to address persistent gaps in rural health care, quality, and sustainability. The program, established under H.R. 1—the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (Public Law 119-21), authorizes $50 billion over five fiscal years (FY 2026–2030) to support comprehensive rural health system transformation, with all funds required to be spent by October 1, 2032.

RHT funding is evenly divided between two components. Baseline funding, totaling $25 billion, is distributed equally among all states with approved applications, resulting in a statutory obligation of $100 million per state per year since all 50 states were approved. States apply once to receive baseline funding for the full program period.

The remaining 50 percent is awarded through Workload Allocation Funding, a discretionary portion administered by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Total state awards reflect the sum of baseline and workload funding.

To determine states' award amounts, proposals were assessed using two criteria:

- Rural Facility and Population Factors, which are evaluated once during the grant cycle

- Technical Score Factors

For more information, see the Distribution and Scoring Methodology chart developed by State Health and Value Strategies in partnership with Manatt Health. Technical Score Factors are reassessed annually to track progress toward each state’s identified initiative goals.

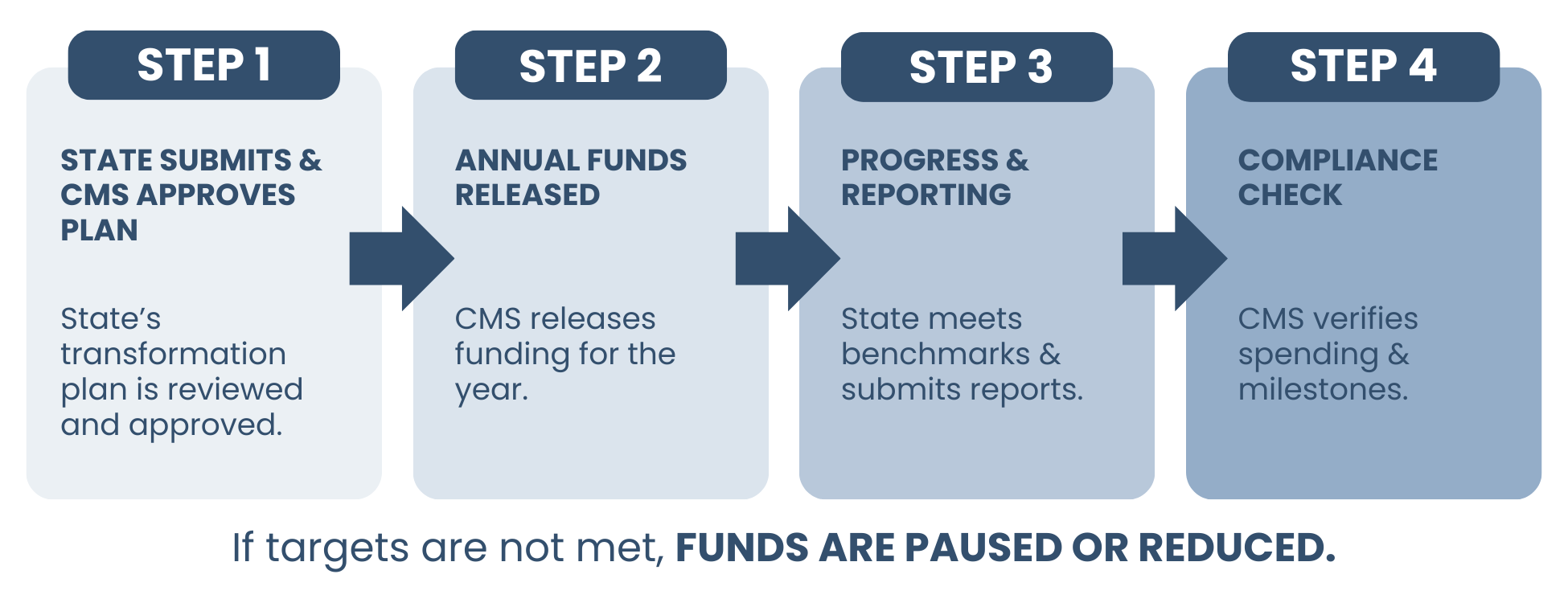

The program is currently in its initial implementation phase

All states have received awards averaging approximately $200 million (See Figure 1), and are now revising budgets to align proposals with final award amounts. CMS requires revised budgets by January 30, with approval within 30 days under cooperative agreements. Funding is released annually rather than upfront, with future allocations contingent on performance benchmarks, reporting compliance, and policy follow-through. As a result, funding levels in years two through five may fluctuate based on technical score reassessments, unspent funds, or failure to meet program requirements.

A review of all 50 state proposals reveals several themes.

Care without walls: Bringing healthcare to where people live

Many states are redefining “access” by decentering the hospital as the primary site of care.

- Mobile clinics, school-based health centers, wellness hubs, and home-based care

- Community paramedicine and Mobile Integrated Health (MIH)

- Health pods, libraries, schools, and faith/community spaces as care sites

Identified in Florida, Ohio, Massachusetts, Vermont, Delaware, Maine, Virginia, Texas, Oklahoma.

This reflects a structural shift toward care delivery that adapts to rural geography, transportation barriers, and workforce shortages.

Maternal health as the entry point for rural health transformation

Maternal and infant health is emerging as a keystone issue—used to justify investments in technology, workforce, and care coordination.

- Regional maternal hubs and hub-and-spoke models

- Remote fetal monitoring, obstetric emergency carts, tele-OB

- Community-based maternal care teams and doulas

Identified in Alabama, Alaska, Georgia, South Dakota, Kentucky, Virginia, New York, California.

Maternal health deserts expose challenges across the entire rural system—EMS, workforce, broadband, and hospital sustainability.

Technology as infrastructure

Technology is no longer framed as innovation for innovation’s sake—it is being positioned as core rural health infrastructure, akin to roads or utilities.

- Statewide digital backbones and shared EHR platforms

- Telehealth hubs, remote patient monitoring, AI decision support

- Drone delivery, pharmacy kiosks, telepharmacy, and virtual-first care

Identified in Hawaii, Wyoming, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Idaho, Texas, Alaska, Mississippi.

States are acknowledging that small, independent rural providers cannot modernize alone, prompting shared platforms, centralized IT, and state-sponsored infrastructure.

Developing local workforce

There is a clear pivot away from recruitment toward “grow-your-own” pipelines rooted in rural communities.

- High school-to-healthcare pipelines

- Rural residencies and clinical rotations

- Tuition assistance tied to rural service

- Expanded roles for CHWs, pharmacists, EMTs, doulas, and peers

Identified in Arizona, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, Vermont, Illinois, Nevada, New Mexico.

States are recognizing that retention follows belonging—providers trained locally are more likely to stay, reducing churn and long-term costs.

From fee-for-service to accountability for outcomes

Value-based care (VBC) is no longer theoretical—many states are designing rural-adapted payment models.

- Capitated primary care models

- APMs tied to reduced ED use and hospitalizations

- “Shadow” VBC programs to prepare providers

- AHEAD-aligned initiatives

Identified in Missouri, South Dakota, Kansas, Nevada, Pennsylvania, Hawaii, Mississippi.

States are confronting the reality that traditional reimbursement accelerates rural hospital failure, while VBC offers flexibility to pay for prevention, coordination, and non-traditional providers.

Regionalization over isolation

States are increasingly designing regional systems of care rather than expecting each rural provider to be fully self-sufficient.

- Hub-and-spoke networks

- Regional collaboratives and coordinating centers

- Shared staffing, reporting, and data systems

Identified in California, Missouri, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Washington, Arkansas.

This reflects a philosophical shift: rural sustainability depends on interdependence, not independence.

Health is being reframed not just as a service—but as critical rural infrastructure that sustains communities, jobs, and population retention.

Rural health as economic development

Several states explicitly link health investments to local economic stability.

- Health tech startup funds

- Workforce pipelines tied to local employment

- Keeping hospitals open as anchor institutions

Identified in Iowa, South Carolina, Kansas, Nevada, Wyoming.

Health is being reframed not just as a service—but as critical rural infrastructure that sustains communities, jobs, and population retention.

Conclusion

Taken together, the first round of Rural Health Transformation Program proposals signals a decisive shift in how states understand and invest in rural health. Rather than trying to preserve legacy systems that have proven unsustainable, states are using RHT funding to redesign care delivery around rural realities—geography, workforce constraints, aging populations, and fragile hospital economics.

The emphasis on care beyond hospital walls, maternal health as a system-wide catalyst, shared technology infrastructure, locally rooted workforce pipelines, value-based payment, regional coordination, and economic development reflects a more holistic and pragmatic vision of rural sustainability.

As CMS moves into annual reassessment and performance-based funding decisions, the success of the RHT Program will hinge on states’ ability to translate these strategies into measurable outcomes, durable partnerships, and policy alignment.