Explore topics and analysis from Community Solutions

Public testimony and policy analysis are the foundations of our policy advocacy work. Research includes reports, consulting, data analysis, and fact sheets. Browse our work by topic, type, or author.

Explore the fact sheets

We make data digestible. Community Solutions produces fact sheets highlighting demographic, health, and social indicators for communities around Ohio. We examine data indicators within poverty, education, employment, income, health outcomes, and public benefit programs. Policymakers and direct service organizations use this resource to better understand the communities they serve and advocate for improved health and social conditions around the state.

Federal Congressional Districts in Ohio

These fact sheets explore demographics, economic stability, food security, housing, education and employment, health, and funding sources in each of Ohio's 15 Federal Congressional Districts. Data from 2025.

Medicaid in Ohio by County

More than 25 percent of Ohio's population receives health care coverage from Medicaid. These fact sheets explore those covered populations, work requirements, and the potential for coverage loss if policy or funding changes are made to the program. Data released 2025.

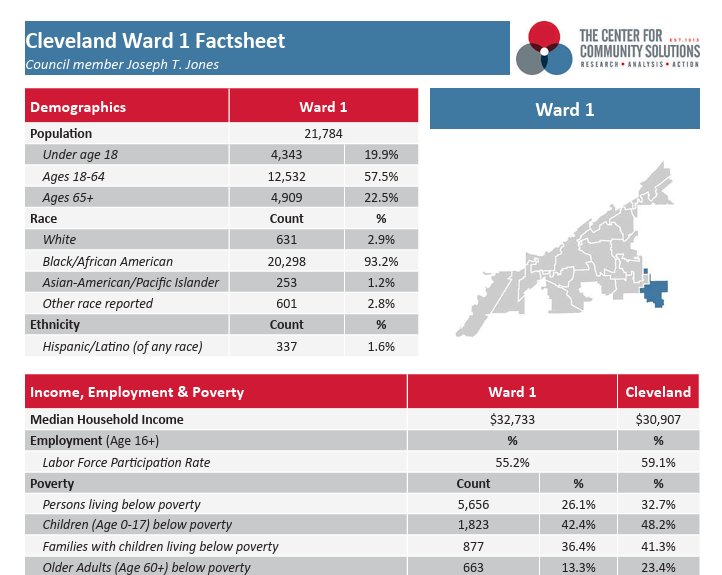

Cleveland Wards

City of Cleveland Ward fact sheets highlight pre-pandemic demographic, health, and social indicators in the City of Cleveland. The fact sheets include basic demographic information about each neighborhood and pre-pandemic data on employment and income, poverty, education, housing and health. Data released 2021 and 2022.

Ohio Legislative Districts

By matching Census block groups with the boundaries of Ohio’s new legislative districts, then to data points from the U.S. Census Bureau, we created fact sheets for each of the 132 legislative districts. Fact sheets include demographic information about each district, as well as district-level data on employment and income, poverty, education, housing, and health. Data released in 2023.

Geauga County Municipalities

These fact sheets and data profiles highlight demographic, health, and social indicators in the cities, townships, and villages of Geauga County. The fact sheets summarize and the data profiles provide extensive information about each Municipality on employment and income, poverty, education, housing, and health. Data released in 2024.

Lake County Municipalities

These fact sheets and data profiles highlight demographic, health, and social indicators in the cities, townships, and villages of Lake County. The fact sheets summarize and the data profiles provide extensive information about each Municipality on employment and income, poverty, education, housing, and health. Data released in 2024.